A Glimpse into the Near Future

A Glimpse into the Near Future: How AIs and Social Media Will Define Elections

Ramon R. Tuazon

Politicians are finding innovative ways to use artificial intelligence (AI) to educate, inform, and even entertain voters as they head to polling precincts. Meanwhile, governments are working to catch up on regulations on the use of AI and social media in the midst of unrelenting technological revolution.

The year 2024 was dubbed by the United Nations (UN) as a global “super year for elections” as 72 countries, including 20 Asian countries, went to the polls. Additional national and local elections were held in 2025 and more will be held in 2026.

Lessons on the issues and challenges in the use of digital technology in the electoral cycle were discussed during the recent Online Roundtable Discussion on Artificial Intelligence, Social Media, and Elections in Asia.

Leading academics and scholars from Bangladesh, Indonesia, Japan, the Philippines, and Thailand shared their analysis on the use of AI and social media in the entire electoral cycle, recalling experiences from recent elections in their respective countries.

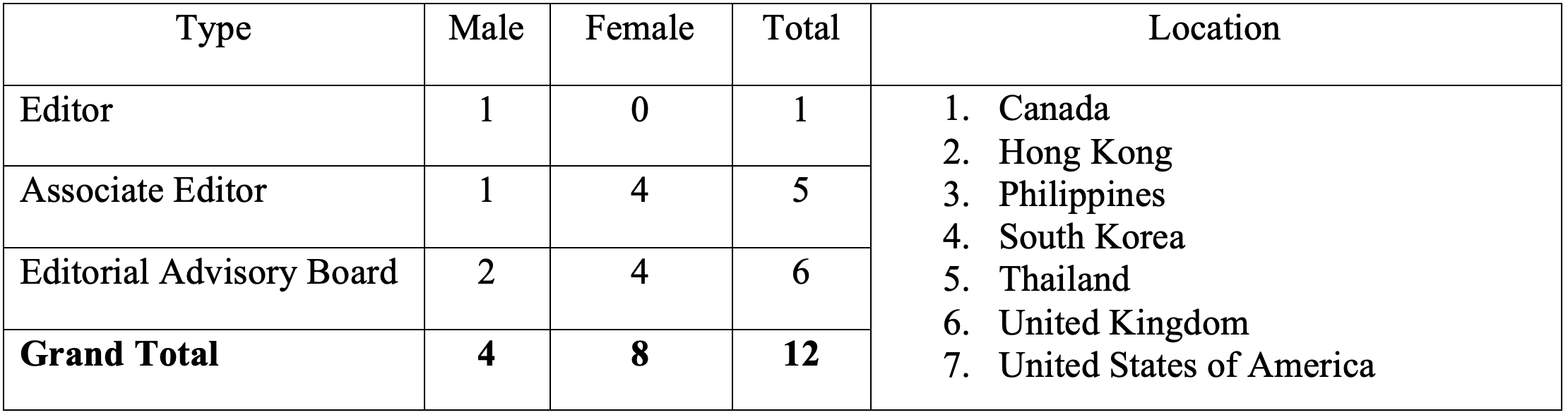

The forum was organized by the Asian Media Information and Communication Centre (AMIC) and the Faculty of Communication Arts of Bangkok-based Chulalongkorn University, in partnership with UNESCO and the Asian Network for Free Elections (ANFREL).

A compelling reason why there is a need to examine electronics and media technology is that without free elections and media freedoms, there can be NO GENUINE DEMOCRACY. As the UNESCO publication, Elections in Digital Times: A Guide for Electoral Practitioners (2022) warned “… the ubiquity of social networks and the impact of Artificial Intelligence can intentionally or unintentionally undermine electoral processes, thereby delegitimizing democracies worldwide.”

Candidates Use AI “To Dance Themselves To Victory.”

Recalling their observations, forum panelists noted that AI is now widely used not only to inform or educate voters but to “entertain” them, as well.

Social media and AI are the platorms of choice in reaching out, especially to Generation Z voters, or those born roughly between the late 1990s and early 2010s.

According to Dr. Wijayanto, Vice Rector for Research, Innovation, Collaboration and Public Communication of the Universitas Diponegoro in Indonesia, AI and social media are being used to “build new image.” He recalled how a leading candidate, who eventually won the election, used AI-generated visuals to rebrand himself as a softer, more approachable figure, often depicting the candidate as a gemoy or cute grandpa.

He cited one specific advertisement which drew attention for featuring a leading political candidate with AI-generated images of children in the background during a milk-feeding event. Providing free milk to children to address malnutrition and stunting in Indonesia was a key component of the candidate’s platform.

To Wijayanto, messages do not always have substance but candidates and political parties “rely on entertainment.” He recalled how some candidates use AI “to dance themselves to victory.” Other issues mentioned by Wijayanto are the use of fake social media accounts or unofficial social media accounts to spread hate speech, and the use of so-called cyber troops.

Cyber troops refer to groups of individuals or teams that use the internet and social media to influence public opinion, manipulate information, and shape narratives for various purposes. Dr. Muneo Kaigo, Dean of the Graduate School of Humanities and Social Sciences of the University of Tsukuba, Japan, noted that candidates hire public relations (PR) companies and social media influencers “to have genuine connection” with the public. But according to Kaigo, such connection does not automatically mean greater public knowledge of policies and programs.

Kaigo acknowledged that new digital technologies can improve access to information and can help ensure free elections. He also cited other benefits or uses of AI and algorithm: the emergence of a 24/7 platform which can answer voters’ questions, and through which candidates and political parties can monitor voters’ opinions and sensitivities on important issues.

However, he warned that AI and social media platforms are also being used as platforms for misinformation, polarisation, and creation of filter bubbles. According to the Japanese academic, because of the widespread use of AI, “AI candidates” or Avatars have emerged. There were also reports on the use of AI-generated deepfakes which can get significant traction in just a few days. University of the Philippines journalism professor Dr. Danilo A. Arao focused on how new digital tools and systems are being used by the “rich and powerful” to maximize their “foothold on power.”

Arao said that there is disinformation and historical denialism in social media and platforms, as he agreed with the Indonesia experience shared by Wijayanto that digital platforms are being used to “repackage” politicians. Arao also lamented that social media is riddled with disinformation, lies, and conspiracy theories. In the Philippines, they are also used to ostracize individuals in social media and real life by engaging in red tagging, i.e., individuals are labelled as communists or communist sympathizers.

John Reiner Antiquerra, Senior Program Officer for Outreach and Communication of the Bangkok-based Asian Network for Free Elections (ANFREL), which observed the 2025 elections in the Philippines and other Asian countries, reported the use of false narratives particularly by pseudo web pages or those not officially identified with political parties.

A related concern expressed by Antiquerra was the use of AI-generated homophobic campaign messages directed at minorities, as observed in Sri Lanka.

Can AI and social media lead to a more informed public or voters? For Arao, no. For him, social media content appeals to “lowest common denominator” or tends to dumb down or trivialize rather than raise the quality of discourse.

For Chulalongkorn University professor emeritus Dr. Pirongrong Ramasoota, “turbulence” best describes the Thai political setting which has become intensified by the growing digital battlefield. According to the Thai academic, there is paradigm shift in political mobilization as social media algorithms, AI analytics and digital “fandoms” became the decisive factors in determining electoral outcomes, eclipsing the traditional influence of money politics and local patronage networks.

New or young politicians use social media extensively, bypassing traditional media.

Ramasoota also noted the emergence of Do-It-Yourself (DIY) political participation (campaigning). However, according to her, conservative politicians are not used to DIY political campaigning. Another phenomenon she observed is the emergence of “fandom” which can be traced to the phenomenal increase in the use of social media platforms TikTok and Facebook.

Fandom usually refers to a group of people (or a community of interest) who share a strong interest or enthusiasm for a particular topic. These fans engage in collaborative activities like group chats, creating fan art, attending events, and participating in online forums or social media groups.

Young people in Bangladesh, who comprise the majority of the population and dominate the use of social media platforms and AI, are major players in the current political system. Dr. S M Shameem Reza, Professor of Mass Communication and Journalism at the University of Dhaka, recalled that in 2024, Bangladesh experienced mass uprising driven by youth activism.

According to Reza, the visual element of social media is an advantage. Even so-called mainstream (legacy) media use social media posts – sharing photos and videos and live-streaming events. Interactive qualities, e.g., like and share, also make these platforms preferred. Reza warned that the use of AI can exacerbate “information asymmetry.” This means AI can widen the gap between those who have access to accurate and timely information and those who do not.

Information asymmetry can happen in several ways: AI-generated dis/misinformation; algorithmic bias; information overload; and lack of transparency, as AI decision-making processes make it hard for people to understand how decisions are made and what information is being used.

Policymaking: Catching Up with the Digital Revolution and a Balancing Act

Crafting policies (especially the government) on digital technologies can be challenging for several reasons. First, policymakers will always be engaged in catching up with new technologies as today’s policies can be easily rendered obsolete, considering the slow government policy-making process. Second, policymakers are not familiar with the new media ecosystem which requires a different kind of regulatory framework. Third, policies are double-edged swords. They can be used to facilitate the enjoyment and exercise of media freedoms and rights but can also be used to narrow or restrict the same rights and freedoms. Fourth, the gold standard in public policymaking is for the process to be open, transparent, and participatory (multistakeholder).

Academics from the five countries represented in the online forum shared their insights on AI and social media policymaking.

According to Kaigo, “there are strict regulations but light enforcement.” The Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications oversees elections and also has jurisdiction over telecommunications and broadcasting industries and local governance. He volunteered that the Public Offices Election Law is under revision.

The Japan Platform Distribution Act, also known as the Information Distribution Platform Act (IDPA) regulates online platforms in Japan. It aims to address issues related to defamation, infringement of rights, and dissemination of harmful information online. Social Media Regulation requires platforms to take swift action against illegal or harmful content and improve transparency in content removal policies.

In the Philippines, prior to the 2025 mid-term election, the Commission on Election (COMELEC) issued Resolution 11064 (dated 17 September 2024) as amended in Resolution 11064-A (dated 13 November 2024) entitled, Guidelines on the Use of Social Media Artificial Intelligence, and Internet Technology for Digital Election Campaign, and the Prohibition and Punishment of Its Misuse for Disinformation and Misinformation In Connection with the 2025 National and Local Elections and the BARMM Parliamentary Elections.

According to Wijayanto, there was no law on the use of AI during the June 2025 election in Indonesia, but new guidelines on the use of AI will hopefully be implemented in the 2029 election. In Thailand, there is no existing specific regulation by the Election Commission of Thailand (ECT) to govern the use of AI and social media during the electoral process beyond labelling posts to show accountability. However, government agencies work closely with major technology platforms like Meta and TikTok. Ramasoota highlighted the need for greater coordination between the ECT and the National Broadcasting and Telecommunications Commission (NBTC).

The Election Commission of Bangladesh is responsible for enforcing the Code of Conduct for Political Parties and Candidates. Some of the key provisions of the code include social media campaigning, e.g., candidates must submit their social media information and adhere to guidelines on content and advertising and prohibited activities such as the use of drones, quadcopters, or similar devices on election day and during campaigning. Disseminating hate speech, personal attacks, and provocative language are also prohibited.

Interesting views on regulatory ecosystem were discussed by some of the panelists.

Ramasoota, a commissioner of the NBTC, raised an important issue: “More regulations may mean more government involvement. Are we ready for this set-up?” According to her, “good regulations come from public participation” and that “regulation need not be top-down especially regulations

on AI.”

Ramasoota called for a “balanced” regulatory ecosystem. This call echoes UNESCO’s Guidelines for the Governance of Digital Platforms (2023) that aims to safeguard the rights to freedom of expression, including access to information, and other human rights in digital platform governance, while dealing with content that can be “permissibly restricted” under international human rights law and standards. The Guideline also introduced the regulatory ecosystem that includes self-regulation, co-regulation, and statutory regulation. The Guideline provides that governance processes should be open, transparent, multistakeholder, proportional, and evidence-based.

For University of the Philippines Professor Arao, self-regulation should be the preferred mechanism as government regulation may lead to “control of media system to fit official narratives.” He proposed that permissible regulatory aspects should focus on corporate/profit (commercial) concerns but not on content.

Moving Forward: Some Policy Options and Action Agenda

Panelists proposed some specific and comprehensive policy options and action agenda.

Among the common specific proposals made were ethical and responsible use of AI, including voluntary labelling of AI materials; prohibiting the use of (AI-generated) deepfake videos; saying no to all forms of disinformation/misinformation; providing no space for hate speech and discrimination against gender, culture, and ethnicity; extending support for and strengthening of independent factchecking initiatives; and promoting more robust media, information, and digital literacy programs.

According to Reza, in terms of timeframe, policies can be immediate (short-term), medium-term, or long-term. Policymaking should be “multi-layered.” He referred to a process where policy decisions are not made in isolation, but rather, are influenced by multiple factors, actors, and levels of governance. Reza emphasized that policymaking should be collaborative, involving different stakeholders including journalists, bureaucrats, politicians, non-government organizations (NGOs), civil society organizations (CSOs), and the academe. “We also need to involve or mainstream local and community media which also need retooling in gender sensitivity, fact checking, deep fakes, etc.,” Reza said.

Reza also emphasized the need to review and update the Code of Conduct for Political Parties and Candidates, not only to update policies on the use of AI and social media during elections, but how to deal with disinformation. Among his recommendations are: (1) conducting independent fact-checking to debunk wrong and harmful information; (2) leveraging AI in fact-checking; (3) advocating Digital and Media and Information Literacy; and (4) pushing for more active participation of stakeholders including media, election groups, and CSOs.

Ramasoota reminded the virtual forum participants that policies should not only focus on technical (technological) but also on the socio-psychological effects of technology. She also expressed the need for more coordination among election commissions, technology agencies, and regulatory agencies, and that policymaking should not be reactive but proactive.

Wijayanto informed the participants of the upcoming Sub-Regional (Southeast Asia) Toolkit for the Implementation of UNESCO Guidelines for Governance of Digital Platforms (2023) which is a collaborative project of the University of Diponegoro (Indonesia), AMIC, and Civic Tech Lab

(Singapore). Capacity building workshops will be held in the Philippines and Indonesia for regulators and civil society organizations.

For Arao, reforming the Philippines’ electoral system requires broader or systemic political reforms, including enactment of Anti-Political Dynasty Law, passage of a Party-list Reform Law, and support for a more vibrant (independent) media.

ANFREL’s recommendations reinforce Arao’s suggestions, as the Asian election watchdog calls on Asian governments to adopt an open data regime to ensure open disclosure of public documents and the passage of Freedom of Information/Right to Information Law. Antiquerra also reiterated the need for an open and transparent policymaking ecosystem. Antiquerra emphasized the need for media, information, and digital literacy as a continuing and long-term strategy.

Lessons Learned

A free and fair election is not only about the freedom to vote; it is also about enabling and providing individuals and groups, especially from marginalized sectors, with platforms and mechanisms to participate in debates, seek clarification on issues, and to talk back to political parties (and candidates) on their concerns, opinions, and needs. This participatory process has been enhanced by the emergence of social media and artificial intelligence which, unfortunately, has been abused by practices described in the preceding paragraphs.

Technology and innovations can be double-edged swords: they can be both beneficial and problematic. The many benefits of AI and social media in the electoral process need more studies and documentation to provide concrete lessons to election stakeholders, including politicians, election management bodies, and the voting public on how to ensure that elections in today’s digital age contribute to public trust and confidence in the electoral process, and of course, in strengthening democracy.

It is important to emphasize an important lesson from the forum. WITHOUT FREE AND FAIR ELECTIONS, DEMOCRACY will just be an illusion. But free and fair elections is endangered by disinformation, misinformation, and hate speech. It is imperative to make sure that TRUTH ALWAYS WINS. (END)